What are we talking about when we imagine a Mythos with no Cultes de Goules or De Vermis Mysteriis? Where Nyarlathotep is just one more faceless, alien outer god – not a singularly sinister entity that truly sees humanity and, at times, seems almost human itself? We are talking about a Mythos without Robert Bloch.

Despite having considered myself “into the Mythos” for more than 30 years now, Robert Bloch was not an author I had read much of or knew much about (see “A Little More on Robert Bloch” below). Recently, at my local used book store, I picked up a copy of the 2nd edition of Mysteries of the Worm, Chaosium’s collection of Bloch’s cosmic horror and Mythos stories. Those stories sufficiently impressed me to do a deeper research and reflection drive. That, in turn, left me sufficiently impressed to put together review of Mysteries of the Worm combined with a short essay on Bloch and his contributions to the Mythos.

Most of the stories in Mysteries of the Worm qualify as Lovecraft Pastiche. That term, “pastiche” (and especially “Lovecraft Pastiche”) is typically used dismissively. Here, that is not my intent. These are stories that are both excellent and enjoyable, but executed in imitative homage to Lovecraft, rather than what we came to know as Bloch’s genuine authorial voice.

It is true that Bloch lacks the raw, weird power of Lovecraft’s imagination. At the same time, for all the idiosyncratic charm of Lovecraft’s writing, though it may be heresy, I argue Bloch is better than Lovecraft at constructing stories and using words. If this collection is pastiche, it is delightful pastiche. That being said, the most memorable stories in Mysteries of the Worm tend to be ones where, among the homage, we can still occasionally hear Bloch speaking as Bloch.

A Little More on Robert Bloch

Robert Bloch (1917-1994) is familiar to most Mythos readers for two reasons:

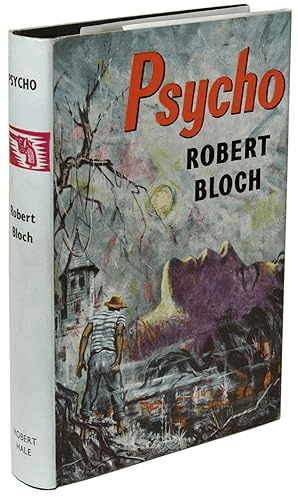

First, he wrote the novel Psycho upon which Hitchcock’s movie was based (not, as is sometimes reported, the screenplay itself). This launched a successful Hollywood career and made Bloch one of the few early Mythos authors to enjoy mainstream success during his lifetime. This recognition included (and, yes, I totally cribbed this from Wikipedia) the Hugo, Bram Stoker, and World Fantasy awards. He served as president of Mystery Writers of America and was a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Secondly, Bloch was the author of the well-known “Shambler from the Stars” a 1935 tale in which, with Lovecraft’s permission, a New England “mystic” clearly intended to be Lovecraft, meets a gruesome end. Lovecraft returned the favor in 1936’s “The Haunter of the Dark,” killing off the story’s protagonist Robert Blake. Dedicated to Bloch, “Haunter” is the only story Lovecraft ever dedicated to a specific individual. Both “Shambler” and the third story in this cycle, Bloch’s 1950 “The Shadow from the Steeple,” are included in Mysteries of the Worm. “Shadow” ties up loose ends from Lovecraft’s “Haunter” while giving readers a chilling glimpse of what Outer God Nyarlathotep is up to in the atomic age.

Through teenage explorations of Weird Tales magazine, Bloch became a great fan of Lovecraft and the two began corresponding in 1933. As he did for many others, Lovecraft became a mentor to Bloch in both the craft of writing and the business of writing.

As an author, cosmic horror in a Lovecraftian vein is something to which Bloch would periodically return throughout his life. But, beginning about the time of Lovecraft’s death in 1937 (a loss which hit the young Bloch very hard) he began moving away from cosmic horror, especially Mythos horror, as a staple of his output. This process was largely complete by the mid-1940s. Among the many kinds of tales Bloch spun in a career spanning more than half a century, he excelled at, and indeed helped establish, the genre of crime horror. While Psycho arguably meets the criteria of crime horror it is “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” which is Bloch’s superlative accomplishment in this regard.

To consider Bloch, as a complete person, a “Mythos author” requires squinting and looking from exactly the right angle. Bloch was not a Mythos author or, more precisely, not only a Mythos author. But Mysteries of the Worm shows why an understanding of the Mythos, especially a literary history of the Mythos, is incomplete without a working knowledge of Bloch’s work and contributions.

Essential Contributions

Mysteries of the Worm certainly can be approached and enjoyed simply as a collection of Mythos and cosmic horror. But for scholars, completionists, and serious fans, the collection has additional value. Mysteries of the Worm highlights exactly how extensive Bloch’s contributions to the Mythos are.

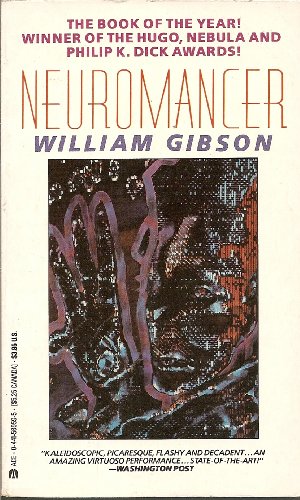

Of the multitude of Mythos tomes, there are four I consider tier-one both for their evocative power and for their ubiquitous and enduring presence in Mythos fiction over the decades: The Necronomicon (of course), Cultes de Goules, De Vermis Mysteriis, and Unaussprechlichen Kulten. We can thank Lovecraft for the first of those, and Howard for the last. The other two, however, are Bloch’s creations.

De Vermis Mysteriis (“Mysteries of the Worm”) and its diabolic author, Ludvig Prinn, first appear in Bloch’s story “The Secret in the Tomb.” Cultes des Goules makes it first appearance in “The Suicide in the Study,” and comes with a much more interesting backstory. The tome’s author, Comte d’Erlette, is not entirely fictional. Rather he is a Tuckerization and alter-ego of fellow Lovecraft Circle member August Derleth (Derleth/d’Erlette).

Depending on who is telling the tale, the unhinged Comte was either a gentle or not-so-gentle dig at Derleth’s rather aristocratic airs. While, strictly speaking, beyond the scope of this article, I can’t resist running down the rabbit hole of the Comte’s literary history a little further. Lin Carter later doubled-down on Bloch’s Tuckerization by ascribing to the Comte the same controversial “war in the heavens” division among Mythos entities utilized by Derleth himself. Derleth, however, may have had the last laugh by using his alter ego in two stories of his own, “Adventure of the Six Silver Spiders” and “The Black Island.”

Traditionally, creation of Nephren-Ka, the cursed Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, whose name was struck from monuments by the priesthoods of his more benign successors, has been ascribed to Lovecraft’s “The Haunter of the Dark” Lin Carter tells us this is not exactly so. According to Carter, Bloch’s story “Fane of the Black Pharaoh,” though not published until 1938, had been written prior to “Haunter in the Dark” and that Lovecraft had already seen, and been impressed by, Bloch’s manuscript prior to writing “Haunter.”

It is Bloch’s extensive use of the Pharaoh which solidifies the connection between Nephren-Ka and Nyarlathotep. Some have interpreted Nephren-Ka as a worshiper or even high priest of Nyarlathotep. Others have seen the Pharaoh as nothing less than an avatar of the Outer God. (I wonder how a greater awareness of Bloch’s take on Nephren-Ka might have influenced my own borrowing of the Pharaoh for my novella “The Dreamquest Beast,” had I been more cognisant of the connection at the time I was writing).

Nyarlathotep is, in several ways, distinct among the Outer Gods of the Mythos. First, he is the only one consistently presented as having a mind and personality in the sense that humans understand those concepts. Second, he is the only Outer God with a genuine and specific interest in humanity, albeit a perverse and malefic one. A case can be made that these unique aspects of Nyarlathotep begin with Bloch’s connection of Nyarlathotep and Nephren-Ka.

About the Collection

Every author has their pet elements which they return to again and again, whether they are consciously aware of it or not. As Mysteries of the Worm makes plain, Bloch is no exception. He is clearly fascinated by Ancient Egypt. Egypt at the time of the Pharaohs, or its trappings transported to other times and places, feature in six stories in the collection, including some of those aforementioned stories which have been so essential in creating Nyarlathotep as we know him. It also seems, of all Lovecraft’s core creations, the idea of ghouls really grabbed Bloch’s imagination. Three tales in Mysteries of the Worm feature ghouls, or creatures so like ghouls as to make no difference.

Many of the collection’s stories feature the elements or flavor of pulp coexisting alongside cosmic horror. These pulp elements are not as pronounced as with Robert E. Howard or Clark Ashton Smith, but sound a frequent beat in Mysteries of the Worm nonetheless.

One thing which separates Bloch’s Lovecraft pastiche from the genuine article is the greater diversity in backgrounds and personalities of the protagonists present in Bloch’s work. This is to the collection’s benefit, helping stories feel more individual and distinct and less like copy/paste templates.

I have not endeavored to comment on every story included in Mysteries of Worm. Rather, I have singled out for mention those which either help illustrate broader trends and patterns in Bloch’s work or are singularly notable for their own merits (or, in one case, lack thereof).

The collection’s beginning is dominated by those tales which are the most strongly Lovecraft pastiche. As discussed earlier, this is not necessarily to their detriment. For the most part, this is good pastiche. The strongest examples, however, serve up their homage with at least a slight twist. “The Faceless God” feels like a Bloch doing a pulpy riff on “Under the Pyramids.” For all its essential Nyarlathotep lore, it is less of a Mythos story than dark pulp with a Mythos macguffin. “The Grinning Ghoul” is very much in the vein of “The Statement of Randolph Carter.” If Carter had the stones to follow Harley Warren into the depths. “The Brood of Bubastis” has the shape and feel of Lovecraft’s “The Rats in the Walls,” but combines an Egyptian twist with outre ideas of prehistoric population migrations which even Robert E. Howard would have envied.

If I had to pick one story in this collection to ‘vote off the island,’ it would be “The Creeper in the Crypt.” There is so much not to love here. A ghoul story that is less effective than Bloch’s similar offerings. A flat and weak point-of-view character who is mostly a passive observer to the story’s events. An ineffective homage to Lovecraft by setting the story in an Arkham that feels nothing like Arkham. Some unfortunate ethnic stereotypes (while common enough in the Lovecraft Circle, something Bloch usually manages to avoid). Yet the story is not without interest as an early example of Bloch’s combining crime fiction with horror, even if not a particularly successful one.

Two stories in Mysteries of the Worm stood out to me for feeling ‘out of time’ with their publication date (coincidentally, in both cases, 1937).

“The Secret of Sebek” is another of Bloch’s Pharaonic Egypt-adjacent tales. This time, however, the setting in New Orleans during Mardi Gras and a secretive masquerade ball of rich weirdos which, of course, conceals a far darker purpose. “Secret” feels far more modern than its publication date. In fact, it feels tailor-made for adaptation as a 1970s giallo film.

“The Mannikin” is a curious story which, at once, looks both forward and back from its 1937 publication date. The set pieces put into place at the story’s beginning are pure Gothic, far more Poe than Lovecraft. The story’s ultimate resolution, however, is very modern. Strip away those set-dressing elements I mentioned, and it is easy to imagine “The Mannikin” as an X-Files episode. Indeed, at the risk of some oblique spoilers, it has significant commonalities with the well-known second-season X-Files episode, “Humbug.”

Mysteries of the Worm presents two of Bloch’s most celebrated short stories, “The Shadow from the Steeple” and “Notebook Found in a Deserted House.”

“Shadow from the Steeple” completes the trilogy begun by Bloch with “The Shambler of the Stars” and then answered by Lovecraft’s “The Haunter of the Dark.” Bloch’s final installment, however, postdates the first two offerings by a decade and half. Published in 1950, it takes classic cosmic horror, very unsettlingly, into the world of nuclear power and the military-industrial complex. Its presentation of a disturbingly human Nyarlathotep, eagerly using those tools and others to bring maximum woe to humanity, is a further example of how much Bloch has influenced our perception of this Outer God.

“Notebook found in a Deserted House,” channels the paranoia and uncertainty of an isolated protagonist as the agents of the Mythos slowly circle in, epitomized in Lovecraft’s “Whisperer in Darkness,” better than almost any cosmic horror story, save the aforementioned HPL tale. Bloch’s literary device of writing in the style of his protagonist, an uneducated farm boy named Willie Osbourn, has been widely acclaimed. Here I admit to being in the minority, I find it distracting (in much the way I find Lovecraft’s occasional attempts at ‘rustic’ dialogue and accents distracting). That may diminish the tale’s impact for me, but certainly does not dissipate it.

Mysteries of the Worm also contains three standout stories which are not as well known as “Notebook” or “Shadow.”

“The Unspeakable Betrothal” is a shining jewel in this collection. Therefore, it is remarkable that Bloch himself considered the story something of a disappointment. For me, “Unspeakable Betrothal” stands out for two reasons. First, excepting Robert E. Howard, it is one of the few examples of a member of the Lovecraft Circle writing a strong, compelling woman with agency (and the protagonist, to boot). Second, it intriguingly explores the questions “What if the otherworldly entities of the Mythos aren’t truly evil or malevolent, what if they are simply alien in the most profound sense of the word?” and “What what if those alien entities tried tried to form a genuine connection with an, admittedly very unusual, human?”

I’ve seen more than a few stories by multiple authors attempting to explore the intersection of photography with the Mythos. Excepting one unfinished, unpublished story shown to me by its author, I had found all of them unsatisfying. Until Bloch’s “The Sorcerer’s Jewel,” which explores that theme with a heavy dose of pulp added to its cosmic horror. Bloch manages to pack in a rich backstory and some truly memorable secondary characters in a fairly short story. I think it is this ability to both sell the reader on the world and make them care about the characters that allows “The Sorcerer’s Jewel” to succeed where so many other stories built around the same premise have failed.

“Terror in Cut-Throat Cove,” the collection’s true stand-out, is also its final selection as well as one of its longest. It delivers Cosmic horror wrapped in pulp that, if not precisely crime horror, is most certainly noir horror. In every way, “Terror” plays to Bloch’s strengths. Unlike some of the other selections in Mysteries of the Worm, in “Terror” Bloch has selected a protagonist which allows the author’s intelligence and broad knowledge to shine through. Originally published in 1959, at a time when Bloch’s career as a screenwriter was still a couple years in the future, nevertheless all those skills enabling Bloch to find success in Hollywood are admirably displayed in “Terror.” Reading the story, it is impossible not to see the screen adaptation unfolding in your mind. “Terror’s” three principal characters are incredibly well detailed, with their interactions and conversation as much character-driven as story-driven (sadly, a rarity even in the best Mythos fiction) and reeking (in the best possible way) of noir rather than cosmic horror. Yet, “Terror” is undeniably cosmic horror. But unlike the Lovecraft pastiche which dominates the collection’s early selections, with “Terror in Cut-Throat Cove,” Mysteries of the Worm concludes with cosmic horror in Bloch’s own voice.

(As a note to interested readers, Chaosium has since released a third edition of Mysteries of the Worm, expanded to include tales not present in the two previous editions)